September 2, 2025

To develop spacecraft that can “maneuver without regret,” the U.S. Space Force is providing $35 million to a national research team, including engineers at the University of Washington. It will be the first to bring fast chemical rockets together with efficient electric propulsion powered by a nuclear microreactor.

The newly formed Space Power and Propulsion for Agility, Responsiveness and Resilience (SPAR) Institute involves eight universities, and 14 industry partners and advisers in one of the nation’s largest efforts to advance space power and propulsion, a critical need for national defense and space exploration.

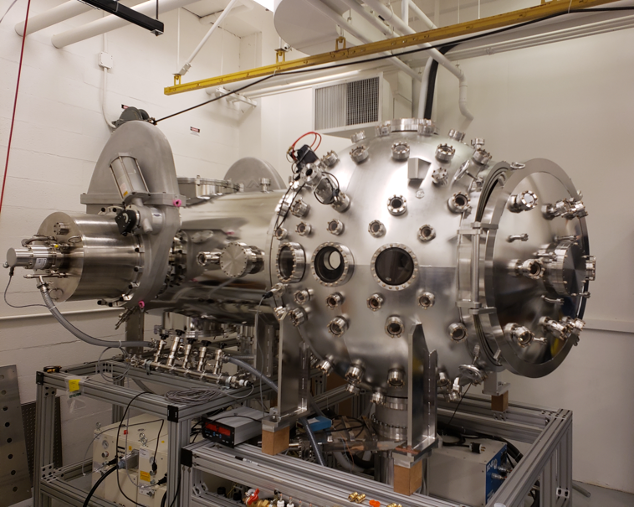

The Space Test Facility at the University of Washington is one of many vacuum facilities used to support the research and development of advanced electric propulsion systems.

Right now, most spacecraft propulsion comes in one of two flavors: chemical rockets, which provide a lot of thrust but burn through fuel quickly, or electric propulsion powered by solar panels, which is slow and cumbersome but fuel efficient. Chemical propulsion comes with the highest risk of regret, as fuel is limited. But in some situations, such as when a collision is imminent, speed may be necessary.

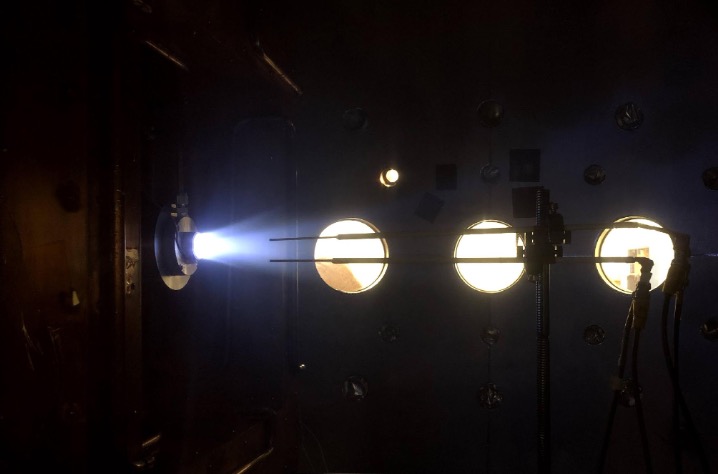

Nuclear microreactors in space could ultimately enable the use of high-power electric propulsion systems for faster, more fuel-efficient spacecraft maneuvers. A central goal of the institute is to develop new electric propulsion technologies that can survive these power levels while also being compatible with different propellant types. The UW Space Propulsion and Advanced Concepts Engineering (SPACE) Lab, housed in the UW’s aeronautics and astronautics department, will be leading research into a high-power electron cyclotron resonance (ECR) thruster, one of three different concepts being pursued by the institute.

Justin Little, SPACE Lab director and associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at the UW, is principal investigator for the ECR thruster subteam. Funding from the SPAR institute will support three UW Ph.D. students to design, build, and test a new thruster that is capable of operating at powers greater than 10 kW – nearly two orders of magnitude higher than existing ECR thruster designs. To eventually provide power to these thrusters in space, industry partner NuWaves will develop new, highly efficient solid-state microwave generators.

The UW SPACE Lab has begun pushing the boundaries of what is possible with ECR thrusters. As part of the SPAR institute, with funding from the U.S. Space Force, the lab will design, build, and test a new thruster that is capable of operating at power levels significantly higher than the current state-of-the-art.

“We are excited to work with our collaborators to expand the possibilities of high-power electric space propulsion,” said Little. “High-power ECR thrusters have the potential to revolutionize how spacecraft move through orbit. The research performed as part of the SPAR institute will allow us to better understand and solve key technological challenges, accelerating the infusion of this technology into the next generation of national defense and space exploration missions.”

Benjamin Jorns, associate professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan, is serving as the director of the institute.

The other universities involved in this project include Colorado State University, Cornell University, Princeton University, University of Colorado Boulder, University of Wisconsin, Western Michigan University, and Pennsylvania State University. Industry partners include Advanced Cooling Technologies, Analytical Mechanics Associates, Antora Energy, Benchmark Space Systems, Cislunar Industries, Champaign Urbana Aerospace, NuWaves Inc., Spark Thermionics, Ultramet, and Ultrasafe Nuclear Corporation.

The advisory board is made up of Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Westinghouse and Aerospace Corp.

This article was adapted with permission from a version written by Katherine McAlpine and published by the University of Michigan.